Pushing the Stone with Open Eyes

How do we keep going when life refuses to make sense?

Many today feel a quiet restlessness — a sense that something fundamental is missing, that no matter how much we do or achieve, a deeper meaning remains just out of reach. What, then, is the point of all this effort? Why continue pushing forward in a world that so often feels indifferent, even disjointed? Even at moments of success, something may feel hollow, as if life refuses to give back a clear answer. This is not failure; it may be the first honest encounter with the absurd.

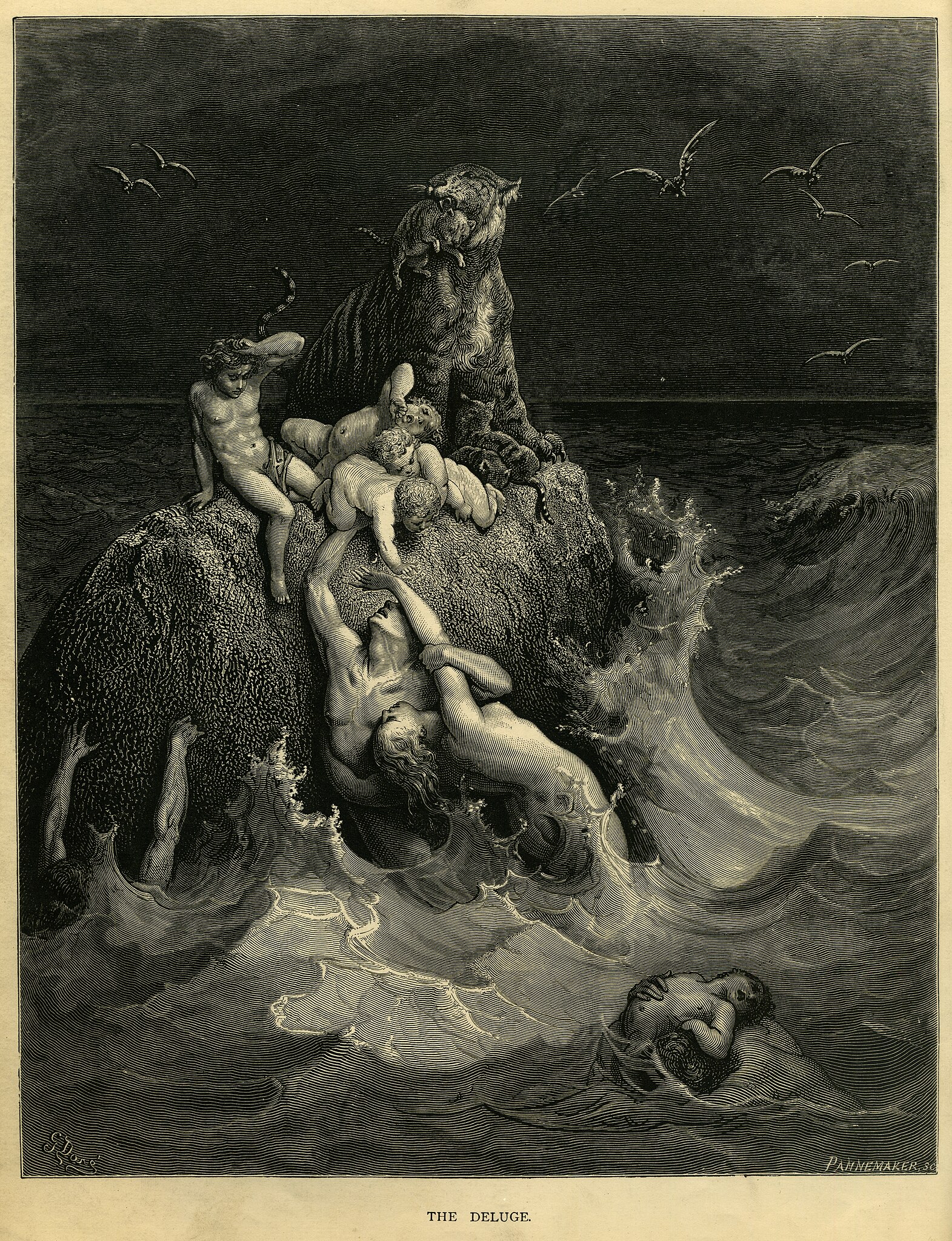

Facing the Absurd

_-_Shade_and_Darkness_-_the_Evening_of_the_Deluge_-_N00531_-_National_Gallery.jpg)

Albert Camus (1913–1960), in The Myth of Sisyphus, begins with what he calls the fundamental question of philosophy:

“There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

This question still resonates today, especially when we find ourselves facing uncertainty, exhaustion, or repetition that seems to lack purpose. In a world where meaning often feels elusive, Camus asks whether life can still be affirmed even if it has no inherent meaning.

“I don’t know whether this world has a meaning that transcends it. But I know that I do not know that meaning and that it is impossible for me just now to know it.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

This is not a confession of ignorance, but a kind of existential starting point — the recognition of the absurd: the space between our yearning for clarity, unity, and purpose, and a universe that offers none.

“Man stands face to face with the irrational. He feels within him his longing for happiness and for reason. The absurd is born of this confrontation between the human need and the unreasonable silence of the world.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

Camus uses the word absurd to name precisely this tension: the meeting of our desire for coherence and the indifference of the universe to that desire. The absurd is not an idea to be defined, but a condition to be lived.

The Choice Before Us

From this recognition of the absurd, human beings face a stark choice. Some may turn to physical suicide, concluding that if life has no inherent meaning, it is better not to live. Others may seek escape in philosophical suicide, turning to faith, metaphysics, or hope to pretend the absurd does not exist. Camus, however, presents a third path: to live fully, lucidly, and without illusion in the face of the absurd.

To embrace this awareness without fleeing it is, he argues, a rare accomplishment — a heightened state of consciousness that those who escape into either form of suicide cannot grasp. The individual who chooses this path becomes what Camus calls the absurd hero — one who revolts against the absurd condition itself: a conscious decision to live, to struggle, and to confront life with clarity, even though that clarity will never be complete.

“It [the revolt] is a constant confrontation between man and his own obscurity. It is an insistence upon an impossible transparency. It challenges the world anew every second — it is not aspiration, for it is devoid of hope. That revolt is the certainty of a crushing fate, without the resignation that ought to accompany it.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

This revolt leads to rebellion — the attempt to reshape human existence through one’s own efforts. The absurd hero recognizes the absurd and rejects suicide despite the suffering and despair of a life without inherent meaning. He embraces the struggle.

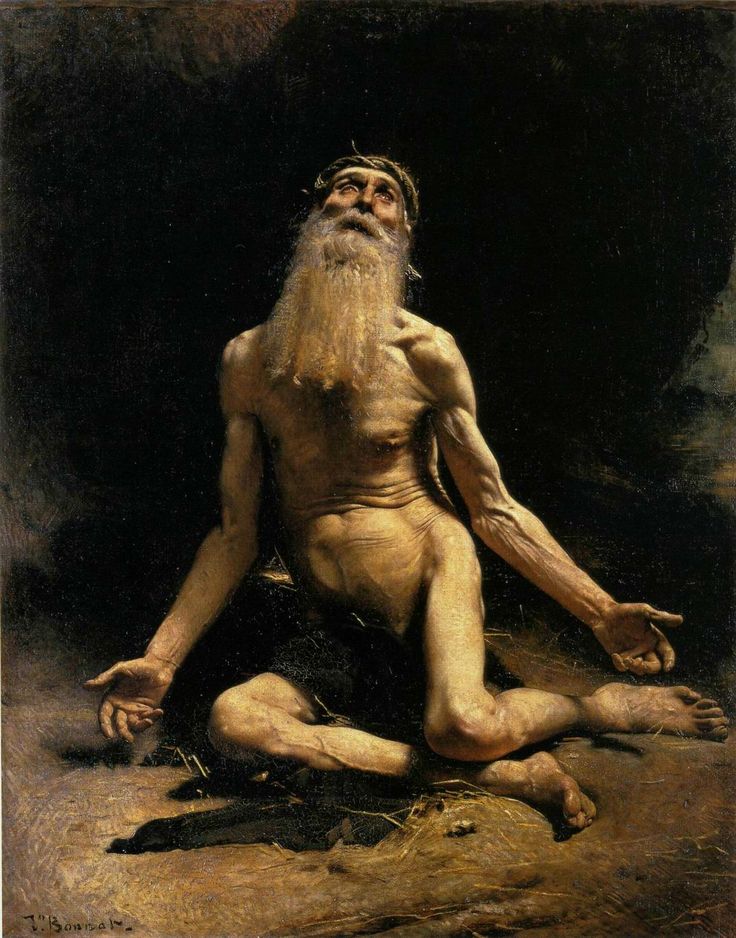

Sisyphus and the Revolt

In Greek mythology, Sisyphus was condemned by the gods to eternally roll a boulder up a steep hill, only to have it roll back down. In Camus’ interpretation, the meaning of this punishment lies in Sisyphus’ full awareness: he not only sees the boulder roll back, but he follows it, descending the mountain fully conscious of the labor he must undertake again. In that descent, he experiences the absurdity of his task, the inevitability of repetition, and the weight of his struggle — yet he does not surrender to despair or seek consolation in illusion. He accepts the absurd, continues his labor, and finds a form of happiness in the effort itself, in the revolt against the inevitability of his condition.

“[The brief period when Sisyphus descends the mountain] is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks towards the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

At that subtle moment when a man glances backward over his life:

“All Sisyphus’ silent joy is contained therein. His fate belongs to him. His rock is his thing.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

Sisyphus knows himself to be the master of his days; he takes ownership of his existence. Camus offers a shift in perspective: the struggle itself can be noble, and clarity — not hope — is our power. This revolt is internal, quiet, and often invisible. It does not deny reality, but embraces it with conscious fidelity. The image of Sisyphus is no longer punishment, but a metaphor for human dignity:

“The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

There is something quietly profound in this view: that clarity, not comfort, gives strength. That even without a promised reward, the act of living deliberately — without illusion, without denial — has value in itself. That happiness is not the result of success, resolution, or transcendence, but of lucidity, ownership, and defiance. The absurd hero does not escape fate; he becomes stronger than it. This may speak to a quiet truth many feel but rarely voice: that continuing in the face of uncertainty can be a form of meaning.

Meaning as Response: Camus and Frankl

Viktor Frankl (1905–1997), Austrian neurologist, psychiatrist, and Holocaust survivor, approached a similar question from a different angle:

“Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the right answer to its problems and to fulfill the tasks which it constantly sets for each individual.”

Viktor E. Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning

For Frankl, life is not something we ask questions of; it is something that asks of us. Rather than seeking meaning from the world, we are called to respond to the demands it places before us, and through our actions and choices, we are responsible for the answers we give to life.

“Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible.”

Viktor E. Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning

Even in the most dehumanizing circumstances, as he experienced in the concentration camps, Frankl observed that one freedom remains: the freedom to choose one’s attitude, to determine one’s response.

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Viktor E. Frankl, Man's Search for Meaning

At first glance, Camus and Frankl may seem opposed: one asserts that life is absurd and offers no inherent meaning; the other insists that life always holds meaning, even in suffering. Yet both reject nihilism, both refuse resignation, and both affirm human dignity in response. Camus calls this stance revolt; Frankl calls it responsibility. In essence, both arise from the same space: the silence of the world and the freedom of the human spirit.

Living Responsibly: Cicero’s Four Personae

Living responsibly, however, does not mean living unhappily. On the contrary, happiness, in the classical sense, arises as a byproduct of living a virtuous and dutiful life in harmony with nature and reason — as long as one is not merely acting but being the author of one’s own identity in an ethically responsible way.

Perhaps Marcus Tullius Cicero’s (106–43 BCE) four personae (roles), as described in his ethical treatise De Officiis (On Duties), can offer a framework for a life that unites responsibility, purpose, and inner harmony. Through these personae, Cicero provides a moral architecture in which strength of character, grounded in both universal and personal duty, cultivates resilience against fortune and opens the possibility of true happiness.

The four personae are:

- The Universal Persona — the shared human capacity for reason and morality, which dictates the universal duties of justice and harmony with nature, supporting the human community and respecting the dignity of all.

- The Individual Persona — one’s unique talents, temperament, and inclinations, which dictate that each person cultivate and employ their own gifts effectively, without violating universal moral duties.

- The Circumstantial Persona — the roles shaped by external conditions such as family, society, and nation, which impose particular responsibilities, provided they do not contradict universal moral principles.

- The Chosen Persona — the path one freely selects, such as a profession or way of life, to be pursued honorably and diligently, aligned with both individual nature and higher moral obligations.

A person who understands their universal duty to justice, aligns it with their natural abilities, fulfills circumstantial obligations responsibly, and pursues a chosen path with integrity achieves inner coherence — a harmony of reason and character that steadies them against misfortune.

A life guided by duty makes one resilient to the whims of fate. When happiness arises from inner virtue — from duty fulfilled rather than from the pursuit of external goods like wealth or power — one becomes free from the fear of loss. The morally steadfast person is the truly free person. Such freedom is not a license to do as one pleases, but the rational capacity to become the best version of oneself — to live consistently, purposefully, and in harmony with universal nature and one’s unique place within the human community.

The duties of the lower personae must never contradict those of the higher; all should ultimately align with the supreme moral law of the universal persona. In this harmony, Cicero finds the foundation of moral peace — a life lived deliberately, dutifully, and therefore joyfully.

Clarity as Beginning

In an age marked by uncertainty, burnout, and quiet disorientation, the recognition that meaning is not found but made — through clarity, responsibility, and harmony with one’s nature — can be quietly liberating. It offers not the comfort of answers, but the steadiness of awareness: the realization that life, even in its ambiguity, continues to ask something of us.

Perhaps, as Camus reminds us, we do not need assurance that things will improve or that purpose will reveal itself. It may be enough to live attentively, to push the stone with open eyes, to meet the silence of the world with our own clear persistence.

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays

And perhaps this clarity — fragile, unpromising, yet fully awake — is enough to begin again.