Between Progress and Restlessness:

Artificial Intelligence and the Search for the Human

The Ambitions of OpenAI

In January 2025, OpenAI, the creators of ChatGPT, published a letter introducing the Stargate Project—a $500 billion artificial intelligence infrastructure initiative described as a necessary step toward the development of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI):

“All of us look forward to continuing to build and develop AI… for the benefit of all of humanity. We believe that this new step is critical on the path, and will enable creative people to figure out how to use AI to elevate humanity.”

OpenAI, Announcing the Stargate Project

This marked a turning point: artificial intelligence was no longer seen merely as a subject of theoretical speculation, but as a plausible mid-term goal in the pursuit of AGI.

But should we be worried? The question seems simple, but it touches on the core of our times.

Demis Hassabis, a 2024 Nobel laureate and CEO and co-founder of Google DeepMind, when asked in an interview “What keeps you up at night?”, replied:

“For me, it's this question of international standards and cooperation—not just between countries, but also between companies and researchers as we get towards the final steps of AGI. And I think we're on the cusp of that. Maybe we're five to ten years out. Some people say shorter... But either way, it's coming very soon. And I'm not sure society's quite ready for that yet.”

Demis Hassabis, interview with Time magazine correspondent Billy Perrigo

GenAI and AGI: Two Different Visions

Being two distinct concepts in the field of artificial intelligence, Generative AI (GenAI) and Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) differ primarily in their scope, capabilities, and stage of development.

While GenAI is a current technology focused on creating new content by recognizing learned patterns, AGI represents a hypothetical stage in which a system can match or exceed human cognitive abilities in any task—including novel, unfamiliar ones—without retraining, and is capable of true creativity.

The dreams of AI enthusiasts, like all technology, carry the potential for both good and harm. Many scientists, though they agree that this development would fundamentally transform society, remain uncertain about the choices they face in this race between countries and companies—a race driven by incentives for profit and power; between the risk of AGI spiraling out of control and the risk of falling behind; between building too fast and not building fast enough.

Dario Amodei, co-founder and CEO of Anthropic and a leading AI researcher, posed a haunting thought experiment in an interview with The Economist’s editor-in-chief, Zanny Minton Beddoes:

“If someone dropped a new country into the world—ten million people smarter than any human alive today—you know, you'd ask the question, 'What is their intent? What are they actually going to do in the world, particularly if they're able to act autonomously?'”

Dario Amodei, interview with The Economist editor-in-chief Zanny Minton Beddoes

The Mirror of Decadence

Today’s Generative AI, though still relatively new, is already being used to spread misinformation through AI-generated websites, newsbots, and chatbots.

It is also threatening the livelihoods of creative workers across various domains: music composed entirely from scratch by AI, short hypnotic videos designed for engagement, and an influx of AI-generated books, images, and articles.

New artists are losing the opportunities once provided by institutions that invested time, money, and energy into discovering and developing human talent.

Existing regulations govern the development and deployment of artificial intelligence, but they do not adequately address its impact on our cognitive, social, and emotional lives.

To understand many of the paradoxes in AI’s development, Jacques Barzun’s observation of a decadent era, which he used to describe Western culture at the end of the 20th century, may provide a useful framework:

“It implies in those who live in such a time no loss of energy or talent or moral sense. On the contrary, it is a very active time, full of deep concerns, but peculiarly restless, for it sees no clear lines of advance. The forms of art as life seem exhausted; the stages of development have been run through. Institutions function painfully. Repetition and frustration are the intolerable result. Boredom and fatigue are the great historical forces.”

Jacques Barzun, From Dawn to Decadence (2000)

Much like Barzun’s decadent societies, the modern race toward AGI is marked by intense, almost feverish production—aimed less at achieving new capabilities than at maximizing efficiency and reducing cost. The result: a culture of “more of the same” characterized by perpetual hype and iteration, rather than patient, foundational research.

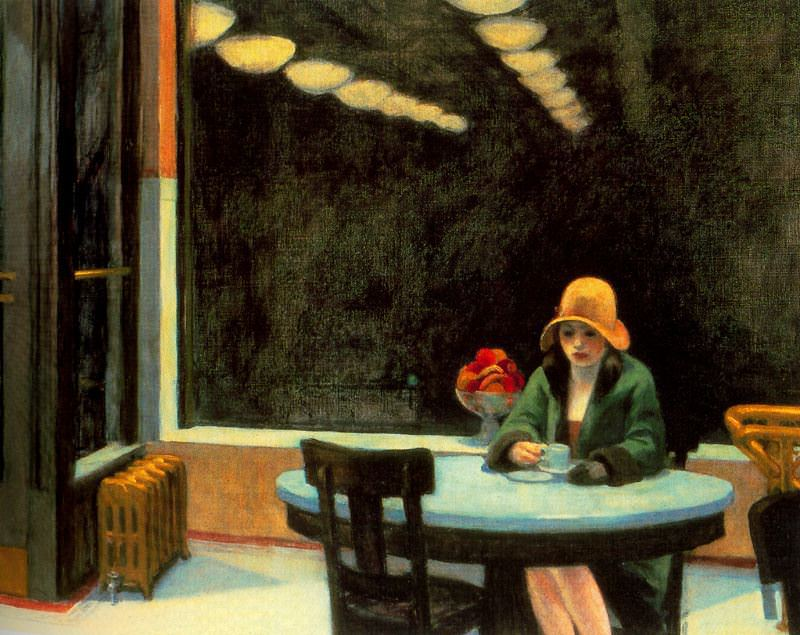

This relentless momentum creates a restless atmosphere, as humans search for meaning beyond merely building or serving the technology. The obsession with the next great leap is driven by technological possibility, not by a clear vision of how it will serve humanity.

And as AI begins to surpass human intelligence in areas such as creativity and problem-solving, the human version of these qualities feels diminished—awakening a sense of boredom that compels us to confront existential questions for which we have no answers, and leaving us in a state of quiet restlessness.

It is a state of existential uneasiness and anxiety—a feeling of becoming, as T. S. Eliot put it, “hollow men”:

“Shape without form, shade without colour,

Paralysed force, gesture without motion.”

And as human relevance is slowly eclipsed by machine efficiency, the world itself seems to fade:

“This is the way the world ends—

T. S. Eliot, “The Hollow Men”

Not with a bang but a whimper.”

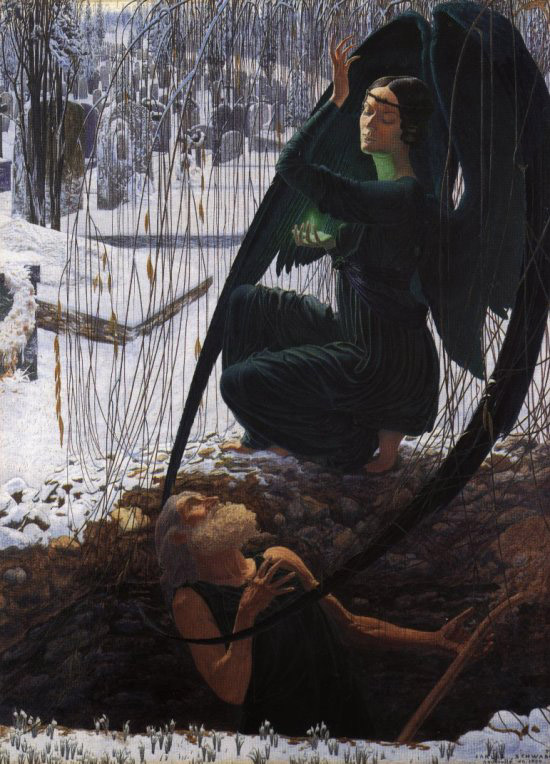

Yet even as the spirit of our modern society slowly erodes, its structures of power may endure for a long time—sustaining an outward show of strength while hollowing out within.

Like the Roman Empire in its later centuries, our civilization may be entering a phase of drawn-out decline: stable on the surface, but sustained more by inertia than vitality.

The poet W. H. Auden, in his 1952 review of Eleanor Clark’s Rome and a Villa, saw in ancient Rome a haunting reflection of our own world:

“…the Roman Empire is like a mirror in which we see reflected the brutal, vulgar, powerful yet despairing image of our technological civilization. What fascinates and terrifies us about the Roman Empire is not that it finally went smash, but that it managed to last for four centuries without creativity, warmth, or hope.”

W. H. Auden, review of Rome and a Villa (1952)

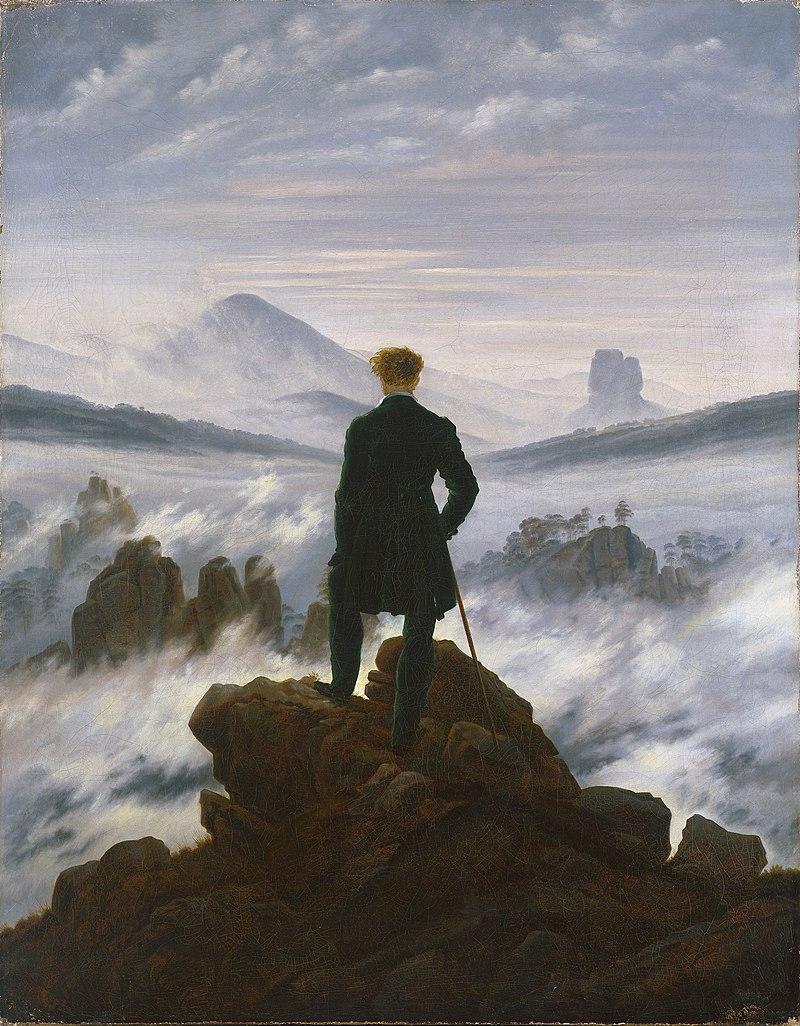

Restlessness and Renewal

Although the most obvious and direct harm of AI is economic, its disruptive effects will transform our lives in ways we cannot yet understand—for better or for worse.

In times of rapid technological and social acceleration, the idea of inner orientation becomes essential. It is not a matter of intellect or knowledge, but about an inner compass — the ability to discern what truly matters and to find direction amid abundance and distraction.

Without it, progress risks becoming movement without meaning, innovation without insight, and we, restless amid achievement, lose our sense of purpose.

Yet, the anxiety and restlessness we feel may still become a force for renewal—if we turn our focus once more to the human half of the equation, by a collective shift in the mindset, values, and psychological outlook of individuals, through conscious choices that cultivate wisdom, ethical reasoning, and empathy.

As AI becomes an autonomous, deterministic force shaping every aspect of human life, Jacques Ellul’s observation gains new relevance:

“The first step in the quest, the first act of freedom, is to become aware of the [technological] necessity.”

Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society (La Technique ou l'Enjeu du siècle) (1954)

A force through which AI, by its own internal logic, shapes our thinking, values, and way of life, often without our awareness. True freedom, then, begins with awareness — with the courage to see the constraints of our time clearly and to act responsibly within them, reintroducing a conscious, human element into a world that is becoming increasingly automated and dehumanized.

In the end, this movement toward inner awareness represents perhaps the most meaningful response we can offer — a form of self-governed action, a higher degree of freedom that generates change from within. It leads, finally, to what Carl Jung described as the achievement of personality:

“Such problems are never solved by legislation or by tricks. They are solved only by a general change of attitude. And the change does not begin with propaganda and mass meetings, or with violence. It begins with a change in individuals. It will continue as a transformation of their personal likes and dislikes, of their outlook on life and of their values, and only the accumulation of these individual changes will produce a collective solution.”

Carl Jung, Psychology and Religion (1938)